The Art and Architecture Movement Known as Constructivism Arose in Which Place and Time

Constructivist architecture was a constructivist manner of mod architecture that flourished in the Soviet Wedlock in the 1920s and early 1930s. Abstract and ascetic, the movement aimed to reflect modernistic industrial social club and urban space, while rejecting decorative stylization in favor of the industrial assemblage of materials.[1] Designs combined advanced applied science and engineering with an avowedly communist social purpose. Although information technology was divided into several competing factions, the movement produced many pioneering projects and finished buildings, before falling out of favour around 1932. It has left marked effects on later developments in compages.

Definition [edit]

Shukhov Tower, Moscow, 1922. Currently nether threat of demolition, but with an international campaign to salve information technology.[2]

Constructivist compages emerged from the wider Constructivist art movement, which grew out of Russian Futurism. Constructivist art had attempted to apply a three-dimensional cubist vision to wholly abstract non-objective 'constructions' with a kinetic element. Afterwards the Russian Revolution of 1917 information technology turned its attentions to the new social demands and industrial tasks required of the new regime. Two singled-out threads emerged, the first was encapsulated in Antoine Pevsner'south and Naum Gabo's Realist manifesto which was concerned with space and rhythm, the second represented a struggle within the Commissariat for Enlightenment between those who argued for pure art and the Productivists such as Alexander Rodchenko, Varvara Stepanova and Vladimir Tatlin, a more socially-oriented group who wanted this art to be absorbed in industrial product.[3]

A carve up occurred in 1922 when Pevsner and Gabo emigrated. The movement so developed along socially utilitarian lines. The productivist majority gained the back up of the Proletkult and the magazine LEF, and later became the dominant influence of the architectural group O.Due south.A.

A revolution in compages [edit]

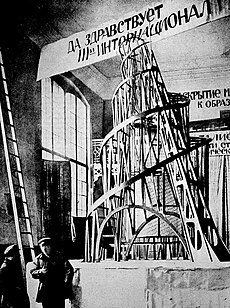

The starting time and most famous Constructivist architectural project was the 1919 proposal for the headquarters of the Comintern in St Petersburg by the Futurist Vladimir Tatlin, often called Tatlin'south Belfry. Though it remained unbuilt, the materials—glass and steel—and its futuristic ethos and political slant (the movements of its internal volumes were meant to symbolise revolution and the dialectic) set the tone for the projects of the 1920s.[four]

Another famous early Constructivist projection was the Lenin Tribune by El Lissitzky (1920), a moving speaker's podium. During the Russian Civil State of war the UNOVIS group centered on Kasimir Malevich and Lissitzky designed diverse projects that forced together the 'not-objective' brainchild of Suprematism with more than commonsensical aims, creating ideal Constructivist cities— meet also El Lissitzky's Prounen-Raum, the 'Dynamic Metropolis' (1919) of Gustav Klutsis; Lazar Khidekel's Workers Club (1926) and his Dubrovka Ability Plant and start Sots Town (1931–33).

ASNOVA and Rationalism [edit]

Immediately after the Russian Civil War, the USSR was likewise impoverished to commission any major new building projects. Nonetheless, the Soviet advanced schoolhouse Vkhutemas started an architectural wing in 1921, which was led by the architect Nikolai Ladovsky, which was called ASNOVA (clan of new architects). The teaching methods were both functional and fantastic, reflecting an interest in Gestalt psychology, leading to daring experiments with form such as Simbirchev'southward glass-clad suspended eating place.[5] Among the architects affiliated to the ASNOVA (Association of New Architects) were El Lissitzky, Konstantin Melnikov, Vladimir Krinsky and the young Berthold Lubetkin.[half dozen]

Projects from 1923 to 1935 like Lissitzky and Mart Stam'south Wolkenbügel horizontal skyscrapers and Konstantin Melnikov's temporary pavilions showed the originality and ambition of this new group. Melnikov would blueprint the Soviet Pavilion at the Paris Exposition of Decorative Arts of 1925, which popularised the new style, with its rooms designed by Rodchenko and its jagged, mechanical class.[4] Another glimpse of a Constructivist lived environment is visible in the popular science fiction film Aelita, which had interiors and exteriors modelled in angular, geometric way past Aleksandra Ekster. The state-run Mosselprom department store of 1924 was besides an early on modernist edifice for the new consumerism of the New Economical Policy, as was the Vesnin brothers' Mostorg store, built iii years later. Modern offices for the mass press were besides popular, such as the Izvestia headquarters.[7] This was built in 1926–seven and designed by Grigori Barkhin[8]

OSA [edit]

Barsch/Sinyavsky, Moscow Planetarium, 1929

A colder and more technological Constructivist style was introduced past the 1923/four glass function project by the Vesnin brothers for Leningradskaya Pravda. In 1925 the OSA Group, also with ties to Vkhutemas, was founded by Alexander Vesnin and Moisei Ginzburg—the Organisation of Gimmicky Architects. This group had much in mutual with Weimar Germany'southward Functionalism, such as the housing projects of Ernst May.[four] Housing, especially collective housing in specially designed dom kommuny to supervene upon the collectivised 19th century housing that was the norm, was the master priority of this group. The term social condenser was coined to describe their aims, which followed from the ideas of V.I. Lenin, who wrote in 1919 that "the real emancipation of women and existent communism begins with the mass struggle against these footling household chores and the true reforming of the mass into a vast socialist household."

Collective housing projects that were built included Ivan Nikolaev's Communal House of the Fabric Institute (Ordzhonikidze St, Moscow, 1929–1931), and Ginzburg'due south Moscow Gosstrakh flats and, well-nigh famously, his Narkomfin Building.[8] Flats were built in a Constructivist idiom in Kharkiv, Moscow and Leningrad and in smaller towns. Ginzburg as well designed a authorities building in Alma-Ata, while the Vesnin brothers designed a Schoolhouse of Film Actors in Moscow. Ginzburg critiqued the thought of edifice in the new society being the aforementioned as in the onetime: "treating workers' housing in the same way equally they would conservative apartments...the Constructivists nonetheless arroyo the aforementioned trouble with maximum consideration for those shifts and changes in our everyday life...our goal is the collaboration with the proletariat in creating a new way of life".[ix] OSA published a magazine, SA or Contemporary Compages from 1926 to 1930. The leading rationalist Ladovsky designed his own, rather dissimilar kind of mass housing, completing a Moscow apartment block in 1929. A particularly extravagant instance is the 'Chekists Hamlet' in Sverdlovsk (at present Yekaterinburg) designed by Ivan Antonov, Veniamin Sokolov and Arseny Tumbasov, a hammer and sickle shaped collective housing complex for staff of the People's Commissariat for the Internal Affairs (NKVD), which currently serves as a hotel.

The everyday and the utopian [edit]

Narkomfin Building in Moscow by Moisei Ginzburg before its restoration in 2020. The building was at the pinnacle of UNESCO'due south 'Endangered Buildings' list, and there was an international campaign to save it.

The new forms of the Constructivists began to symbolise the project for a new everyday life of the Soviet Union, and then in the mixed economy of the New Economic Policy.[10] State buildings were synthetic like the huge Gosprom circuitous in Kharkiv[11] (designed past Serafimov, Folger and Kravets, 1926–8) which was noted by Reyner Banham in his Theory and Pattern in the Showtime Machine Historic period as being, along with the Dessau Bauhaus, the largest calibration Modernist work of the 1920s.[12] Other notable works included the aluminum parabola and glazed staircase of Mikhail Barsch and Mikhail Sinyavsky'south 1929 Moscow Planetarium.

House of Printing (1935) in Kazan past Semen Pen

The popularity of the new artful led to traditionalist architects adopting Constructivism, equally in Ivan Zholtovsky's 1926 MOGES ability station or Alexey Shchusev's Narkomzem offices, both in Moscow.[13] Similarly, the engineer Vladimir Shukhov's Shukhov Tower was often seen every bit an avant-garde piece of work and was, according to Walter Benjamin in his Moscow Diary, 'unlike any like construction in the West'.[fourteen] Shukhov also collaborated with Melnikov on the Bakhmetevsky Bus Garage and Novo-Ryazanskaya Street Garage.[4] Many of these buildings are shown in Sergei Eisenstein's film The General Line, which also featured a specially congenital mock-upward Constructivist collective farm designed past Andrey Burov.

A key aim of the Constructivists was instilling the avant-garde in everyday life. From 1927 they worked on projects for Workers' Clubs, communal leisure facilities usually built in manufacturing plant districts. Among the almost famous of these are the Kauchuk, Svoboda and Rusakov clubs by Konstantin Melnikov, the club of the Likachev works past the Vesnin brothers, and Ilya Golosov's Zuev Workers' Club.

DniproGES (1932) by Vesnin Brothers

At the same time as this foray into the everyday, outlandish projects were designed such equally Ivan Leonidov's Lenin Found, a high tech piece of work that bears comparison with Buckminster Fuller. This consisted of a skyscraper-sized library, a planetarium and dome, all linked together past a monorail; or Georgy Krutikov'south self-explanatory Flying Metropolis, an ASNOVA project that was intended as a serious proposal for airborne housing. Melnikov Firm and his Bakhmetevsky Bus Garage are fine examples of the tensions between individualism and utilitarianism in Constructivism.

There were also projects for Suprematist skyscrapers chosen 'planits' or 'architektons' by Kasimir Malevich, Lazar Khikeidel - Cosmic Habitats (1921–22), Architectons (1922-1927), Workers Club (1926), Communal Dwelling (Коммунальное Жилище)(1927), A. Nikolsky and L. Khidekel - Moscow Cooperative Found (1929). The fantastical element also institute expression in the work of Yakov Chernikhov, who produced several books of experimental designs—most famously Architectural Fantasies (1933)—earning him the epithet 'the Soviet Piranesi'.

The Sotsgorod and boondocks planning [edit]

Town Hall by Noi Trotsky, Leningrad, 1932–4

Despite the ambitiousness of many Constructivist proposals for reconstructed cities, in that location were adequately few examples of coherent Constructivist town planning. However, the Narvskaya Zastava commune of Leningrad became a focus for Constructivism. Outset in 1925 communal housing was designed for the expanse by architects like A. Gegello and OSA's Alexander Nikolsky, also as public buildings like the Kirov Town Hall by Noi Trotsky (1932–4), an experimental school by Chiliad.A Simonov and a series of Communal laundries and kitchens, designed for the area by local ASNOVA members.[fifteen]

Many of the Constructivists hoped to run into their ambitions realised during the 'Cultural Revolution' that accompanied the first five-year plan. At this point the Constructivists were divided between urbanists and disurbanists who favoured a garden metropolis or linear city model. The Linear Urban center was propagandised by the head of the Finance Commissariat Nikolay Milyutin in his book Sozgorod, aka Sotsgorod (1930). This was taken to a more than extreme level by the OSA theorist Mikhail Okhitovich. His disurbanism proposed a system of one-person or one-family buildings connected by linear ship networks, spread over a huge surface area that traversed the boundaries betwixt the urban and agricultural, in which it resembled a socialist equivalent of Frank Lloyd Wright's Broadacre Urban center. The disurbanists and urbanists proposed projects for new cities such as Magnitogorsk were oft rejected in favour of the more pragmatic German language architects fleeing Nazism, such as 'May Brigade' (Ernst May, Mart Stam, Margarete Schütte-Lihotzky), the 'Bauhaus Brigade' led by Hannes Meyer, and Bruno Taut.

The city-planning of Le Corbusier found brief favour, with the architect writing a 'reply to Moscow' that later on became the Ville Radieuse plan, and designing the Tsentrosoyuz authorities building with the Constructivist Nikolai Kolli. The duplex apartments and commonage facilities of the OSA group were a major influence on his later work. Another famous modernist, Erich Mendelsohn, designed St. petersburg's Red Imprint Material Factory and popularised Constructivism in his book Russland, Europa, Amerika. A 5 Year Plan project with major Constructivist input was DnieproGES, designed by Victor Vesnin et al. El Lissitzky also popularised the style abroad with his 1930 book The Reconstruction of Architecture in Russia.

The end of Constructivism [edit]

The 1932 competition for the Palace of the Soviets, a grandiose projection to rival the Empire State Building, featured entries from all the major Constructivists as well as Walter Gropius, Erich Mendelsohn and Le Corbusier. However, this coincided with widespread criticism of Modernism, which was always difficult to sustain in a nevertheless mostly agrestal country. There was as well the critique that the style merely copied the forms of technology while using fairly routine construction methods.[xvi] The winning entry by Boris Iofan marked the kickoff of eclectic historicism of Stalinist Compages, a way which bears similarities to Post-Modernism in that it reacted against modernist architecture'due south cosmopolitanism, alleged ugliness and inhumanity with a pick and mix of historical styles, sometimes accomplished with new applied science. Housing projects like the Narkomfin were designed for the attempts to reform everyday life in the 1920s, such as collectivisation of facilities, equality of the sexes and collective raising of children, all of which fell out of favour as Stalinism revived family values. The styles of the old world were also revived, with the Moscow Metro in particular popularising the idea of 'workers' palaces'.

A.Kuznetsov, V.Movchan, G.Movchan, L.Meilman, All-Union Electrotechnical Constitute, Moscow, 1927–1930 (video)

By the end of the 1920s Constructivism was the state's dominant architecture, and surprisingly many buildings of this menstruation survive. Initially the reaction was towards an fine art decoesque Classicism that was initially inflected with Constructivist devices, such as in Iofan'due south Business firm on Embankment of 1929–32. For a few years some structures were designed in a composite style sometimes called Postconstructivism.

Subsequently this cursory synthesis, Neo-Classical reaction was totally dominant until 1955. Rationalist buildings were all the same mutual in industrial architecture, but extinct in urban projects. Last isolated constructivist buildings were launched in 1933–1935, such every bit Panteleimon Golosov's Pravda building (finished 1935),[17] the Moscow Textile Institute (finished 1938) or Ladovsky'southward rationalist vestibules for the Moscow Metro. Conspicuously Modernist competition entries were made by the Vesnin brothers and Ivan Leonidov for the Narkomtiazhprom project in Blood-red Square, 1934, another unbuilt Stalinist building. Traces of Constructivism tin can also be found in some Socialist Realist works, for instance in the Futurist elevations of Iofan'south ultra-Stalinist 1937 Paris Pavilion, which had Suprematist interiors by Nikolai Suetin.

Legacy [edit]

Due in role to its political delivery—and its replacement by Stalinist architecture—the mechanistic, dynamic forms of Constructivism were not function of the at-home Platonism of the International Style as it was defined by Philip Johnson and Henry-Russell Hitchcock. Their volume included but ane edifice from the USSR, an electrical laboratory by a government team led by Nikolaev.[18] During the 1960s Constructivism was rehabilitated to a sure extent, and both the wilder experimental buildings of the era (such as the Globus Theatre or the Tbilisi Roads Ministry building Building) and the unornamented Khrushchyovka apartments are in a sense a continuation of the aborted experiment, although under very different conditions. Outside the USSR, Constructivism has often been seen as an culling, more radical modernism, and its legacy can exist seen in designers equally various as Team ten, Archigram and Kenzo Tange, as well every bit in much Brutalist work. Their integration of the advanced and everyday life has parallels with the Situationists, particularly the New Babylon project of Guy Debord and Abiding Nieuwenhuys.

Loftier Tech architecture also owes a debt to Constructivism, virtually obviously in Richard Rogers' Lloyd's building. Zaha Hadid'southward early projects were adaptations of Malevich's Architektons, and the influence of Chernikhov is clear on her drawings. Deconstructivism evokes the dynamism of Constructivism, though without the social aspect, as in the piece of work of Coop Himmelb(l)au. In the late 1970s Rem Koolhaas wrote a parable on the political trajectory of Constructivism called The Story of the Pool, in which Constructivists escape from the USSR in a self-powering Modernist swimming pool, only to die, after being criticised for much the aforementioned reasons as they were under Stalinism, soon after their arrival in the Usa. Meanwhile, many of the original Constructivist buildings are poorly preserved or in danger of imminent demolition.[19]

Gallery [edit]

-

-

Izvestia Building, Moscow (Grigori & Mikhail Barkhin, 1926)

-

-

-

Flats, Zamoskvorechye, Moscow (late 1920s)

-

Melnikov House in Moscow. It is at the pinnacle of UNESCO's list of "Endangered Buildings". There is an international campaign to save it.

-

The Peoples Commissariat For Communication Lines (Ivan Fomin, 1929)

-

-

Narkomfin Building, apartment business firm (Moisei Ginzburg, 1930)

-

Narkomfin Building before its restoration in 2020 (Moisei Ginzburg, 1930)

-

Textile Institute, Moscow (1930–8)

-

Regional administration building, 1930–1932. Novosibirsk.

-

Constructivist buildings and other modernist projects in the former USSR [edit]

Moscow [edit]

- Mosselprom edifice (1925) by Nikolai Strukov

- Bakhmetevsky Omnibus Garage (1927) by Konstantin Melnikov and Vladimir Shukhov

- Kauchuk Factory Society (1929) past Konstantin Melnikov

- Svoboda Manufacturing plant Gild (1929) by Konstantin Melnikov

- Novo-Ryazanskaya Street Garage (1929) by Konstantin Melnikov and Vladimir Shukhov

- Melnikov House (1929) by Konstantin Melnikov

- Narkomfin Edifice (1930) past Moisei Ginzburg and Ignaty Milinis

- Rusakov Workers' Club (1929) by Konstantin Melnikov

- Zuev Workers' Social club (1929) by Ilya Golosov

- Tsentrosoyuz building (1936) by Le Corbusier and Nikolai Kolli

- Gosplan Garage (1936) by Konstantin Melnikov

- ZiL House of Culture (1937) past Vesnin brothers

Leningrad (Saint-Petersburg) [edit]

- Stadium for metal workers "Cerise Profintern" (1927) by [Aleksandr Nikolsky] and [Lazar Khidekel]

- Cherry Flag Fabric Factory (1929) by [Erich Mendelsohn]

- Bolshoy Dom in Leningrad (1932) by Noi Trotsky, Alexander Gegello and Andrey Ol.

- Kirov District House of Soviets (1935) by Noi Trotsky

- Moscow District Firm of Soviets (1935) by Igor Fomin, Igor Daugul and Boris Serebrovsky

- 1st Business firm of Lensovet (1934) past Evgeny Levinson and Igor Fomin

- Club for the shipyard workers in St. petersburg. by [Aleksandr Nikolsky] and [Lazar Khidekel]

- Pumping station. Vasilyeostrovskaya pumping station well-nigh the harbor in Leningrad. Construction (1929-1930)by [Lazar Khidekel]

- Dubrovskiy Electro Power Station S.M. Kirov and Residential settlement Doubrovskaya HPP. Planning and construction of the showtime in the Soviet Union socialist boondocks - sotsrogodok for workers and specialists (1931-1933) by [Lazar Khidekel]

Minsk [edit]

- Government House, Minsk (and similar Oblispolkom in Mogilev) past Iosif Langbard

Kharkiv [edit]

- Derzhprom (1928) past Sergey Serafimov, Samuil Kravets and Marc Folger

- House of Projects (1932) by Sergey Serafimov and Maria Sandberg-Serafimova

- Post Office (1929) by Arkady Mordvinov

Zaporizhia [edit]

- DnieproGES (1932) by Viktor Vesnin and Nikolai Kolli

Sverdlovsk (Ekaterinburg) [edit]

- Builders Club (1929) by Yakov Kornfeld

- House of Printing (1930) by Vladimir Sigov

- 'Gorodok chekistov' (1933) by Ivan Antonov, Veniamin Sokolov and Arseny Tumbasov

- Business firm of Communications (1933) past Kasyan Solomonov

Kuybyshev (Samara) [edit]

- House of Blood-red Army (1930) by Pyotr Scherbachov

- Factory kitchen (1933) past Evgenya Maksimova

- House of Industry (1933) by Vasily Sukhov

Novosibirsk [edit]

- Prombank Dormitory (1927) by I. A. Burlakov

- Polyclinic No. one (1928) by P. Shyokin

- Business Business firm (1928) past D. F. Fridman and I. A. Burlakov

- Aeroflot House (1930s)

- Land Bank (1930) past Andrey Kryachkov

- Rabochaya Pyatiletka (1930)

- Krayispolkom (Regional Assistants Building, 1932) by Boris Gordeev and Sergey Turgenev

- Soyuzzoloto House (1932) by Boris Gordeyev and A. I. Bobrov

- NKVD House (Serebrennikovskaya Street 16) (1932) by Ivan Voronov and Boris Gordeyev

- Novosibirsk Chemical Engineering Technical School (1932) by A. I. Bobrov

- Kuzbassugol Building Circuitous (1933) by D. A. Ageyev, B. A. Bitkin and Boris Gordeyev

- Firm of Kraysnabsbyt (1934) by Boris Gordeev and Sergey Turgenev

- Dinamo Residential Complex (1936) past Boris Gordeyev, S. P. Turgenev, 5. North. Nikitin

- NKVD House (Serebrennikovskaya Street 23) (1936) past Sergey Turgenev, Ivan Voronov and Boris Gordeyev

Not-implemented projects [edit]

- Palace of the Soviets Projection

- Tatlin's Tower projection by Vladimir Tatlin

- Narkomtiazhprom Project

References [edit]

- ^ "Constructivism". Tate Modern . Retrieved 9 April 2020.

- ^ Lord Foster fires upwards campaign to save Shukhov Tower: https://www.theguardian.com/world/2010/april/15/radio-tower-campaign-russia-foster

- ^ Oliver Stallybrass, Alan Bullock; et al. (1988). The Fontana Dictionary of Modern Idea (Paperback). Fontana press. p. 918 pages. ISBN0-00-686129-six.

- ^ a b c d Frampton, Kenneth (2004). Modern compages — a critical history (Paperback) (Third ed.). World of Fine art. p. 376 pages. ISBN0-500-20257-5.

- ^ see the picture here: "Archived re-create". Archived from the original on xv April 2008. Retrieved vii April 2007.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy every bit title (link) - ^ Cooke, Catherine (1990). Architectural Drawings of the Russian Avant Garde (Hardback). Harry N. Abrams, Inc. p. 143 pages. ISBN0-8109-6000-1.

- ^ "Izvestia Building Moscow past Grigory Barkhin". galinsky.com. Retrieved 15 August 2015.

- ^ a b S.N Khan-Magomedov, Pioneers of Soviet Architecture (1988).

- ^ quoted in Art and Revolution ed Campbell/Lynton, Hayward Gallery London 1971

- ^ Meet the discussion in Victor Buchli's, An Archeology of Socialism (2000)

- ^ pictures hither: http://world wide web.kharkov.ua/about/svobody-eastward.htm — Freedom Square, Kharkiv

- ^ Reyner Banham, Theory and Design in the First Machine Age (Architectural Press, 1971), p297.

- ^ "Narkomzem (Agronomics Ministry) Moscow by Aleksey Shchusev". galinsky.com. Retrieved fifteen August 2015.

- ^ Benjamin, Walter, Moscow Diary

- ^ Chto Delat/What is to be Done issue on Narvskaya Zastava: http://www.chtodelat.org/images/pdfs/Chtodelat_07.pdf [ permanent expressionless link ] and as well St Petersburg Wandering Camera on Simonov's school: http://world wide web.enlight.ru/camera/354/index_e.html

- ^ Catherine Cooke, The Advanced.

- ^ Archive photo: "Archived re-create". Archived from the original on 15 April 2008. Retrieved 7 April 2007.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as championship (link) - ^ Illustrated here: "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 15 April 2008. Retrieved vii April 2007.

{{cite spider web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ^ See interview with film manager Isa Willinger here: http://awayfromallsuns.de/de/on_constructivism/

Bibliography [edit]

- Reyner Banham, Theory and Design in the First Machine Age (Architectural Press, 1972)

- Victor Buchli, An Archeology of Socialism (Berg, 2002)

- Campbell/Lynton (eds.), Art and Revolution (Hayward Gallery, London 1971)

- Catherine Cooke, Architectural Drawings of the Russian Advanced (MOMA, 1990)

- Catherine Cooke, The Avant Garde (Advertizement magazine, 1988)

- Catherine Cooke, "Fantasy and Construction: Iakov Chernikhov" (Ad magazine, vol. 59 no. 7–8, London 1989)

- Catherine Cooke & Igor Kazus, Soviet Architectural Competitions (Phaidon, 1992)

- Kenneth Frampton, Modern Architecture: a Critical Introduction (Thames & Hudson, 1980)

- Moisei Ginzburg, Style and Epoch (MIT, 1981)

- Southward. Khan-Magomedov, Alexander Vesnin and Russian Constructivism (Thames & Hudson 1986)

- S. Khan-Magomedov, Pioneers of Soviet Architecture (Thames & Hudson 1988), ISBN 978-0-500-34102-v

- Southward. Khan-Magomedov. 100 Masterpieces of Soviet Advanced Architecture

Russian University of Architecture. M., Editorial URSS, 2005

- Southward. Khan-Magomedov. Lazar Khidekel (Creators of Russian Classical Avant-garde series)

M., 2008

- Rem Koolhaas, "The Story of the Pool" (1977) included in Delirious New York (Monacelli Printing, 1997), ISBN 978-1-885254-00-9

- El Lissitzky, The Reconstruction of Architecture in the Soviet Union (Vienna, 1930)

- Karl Schlögel, Moscow (Reaktion, 2005)

- Karel Teige, The Minimum Dwelling (MIT, 2002)

External links [edit]

- Constructivist architecture on YouTube

- Documentary on Moscow'south Constructivist buildings

- Heritage at Risk: Preservation of 20th Century Architecture and World Heritage — April 2006 Conference past the Moscow Architectural Preservation Society (MAPS)

- Annal Constructivist Photos and Designs at polito.it

- The Moscow Times' Guide to Constructivist buildings

- Guardian commodity on preserving Constructivist buildings

- Constructivism in Compages at Kmtspace

- Entrada for the Preservation of the Narkomfin Edifice

- Constructivist designs at the Russian Utopia Depository

- Constructivism and Postconstructivism at St Petersburg's Wandering Camera

- Short moving-picture show on the heavily Constructivist-influenced buildings that Berthold Lubetkin designed for Dudley Zoo in the 1930s on YouTube

- Czech Constructivism - Villa Victor Kriz [ permanent dead link ]

- Commie vs. Capitalist: Architecture - slideshow past Life mag

harrillsobsed1976.blogspot.com

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Constructivist_architecture

0 Response to "The Art and Architecture Movement Known as Constructivism Arose in Which Place and Time"

Postar um comentário